By: Scott Converse

Process maps can be a valuable tool for your team to better organize

Process Mapping Helps Communication and Analysis

Let’s take a look at an applied case to see how process mapping can be used to help with communication, analysis, or maybe even both.

Helen works for a not-for-profit organization that delivers professional development programs. Her customers are professionals in the workplace that want to take a program to sharpen their skills and increase their competency back at the workplace. There are many processes that she and her team work on to help satisfy her customers’ needs, and one of the processes is enrollment.

The enrollment process includes gathering customer order information about the program they are interested in and making sure that prior to the start of the program, all the resources needed for a successful classroom experience have been set up for the participant. The classroom could be in a building or online.

As a process manager, Helen may decide to create a process map to:

- Communicate to her staff about their roles and responsibilities and use a process map to visually show who’s doing what and when they should do it

- Help describe the standard operating procedures associated with enrollment for new employees

- Help communicate and explain to her boss about the enrollment process and why they need to invest money on technology automation or invest in additional people resources to handle the increased demands of this process

- She might be working with other groups, IT for example, on making changes to the process and use a process map to communicate what those changes should look like

- Lead a cross-functional team on how to streamline and improve the enrollment process and use a process map to make sure everyone’s focused on the same goals for this improvement project

Let’s say for this case she has been assigned to lead a team on improving the enrollment process. There is some customer dissatisfaction about the complexity of the enrollment process, and there is a lot of worker frustration around the excessive re-work, hand-offs, and the time it takes to get an enrollment request completed. Before the group starts problem-solving, Helen wants to make sure that everyone has a shared understanding of the process, so she brings the team together to build a process map.

Four Steps to Build a Process Map

1. Determine how the tool will be used

Helen wants the map to first be used as a communication tool, to ensure that everyone is aligned. Based on what we discussed in the previous article, she wants a high-level process map. Later, she’ll want to use the tool for analysis, to help determine which areas should be the focus of problem-solving and future state changes, and to determine which areas are working well and don’t need to be modified. She’ll want to create a detailed process map for that analysis.

Today, we’ll focus on creating the high-level process map.

2. Determine boundaries

All processes have a beginning and an end, so Helen will want the team to come to agreement on those boundaries. It sounds simple, but frequently one of the characteristics of poorly performing processes is that not everyone agrees on what is the start and end of the process.

To determine the start and end of the process, Helen and her team answer the following questions:

- Does the enrollment process begin when the customer/student begins filling out the online program order form?

- Or is it further upstream when they are trying to choose which of the different programs available for enrollment?

- Or when the customer is trying to determine which educational provider they should choose from the many different available?

- Does the end of the process occur when the customer receives a confirmation message, emailed receipt, or invoice?

- Or is it further downstream, when the student arrives at the opening of the program and has their resources assigned properly, such as workbooks, or their student login account?

- Or does it end when the student has completed the program, the exam, and has earned a certification, showing that they have mastered the skills and tools covered in the course?

A process map doesn’t answer these questions, rather it’s a platform for needed team discussion and decision making.

Pro-Tip: Using Boundaries for Project Scope

When determining boundaries, make sure they contain the activities that concern both the customer and organization. The frustrations of customers and the inefficiencies that process workers deal with should be included in the boundaries from beginning to end. Another way to use boundaries is to help with scoping down the project. By keeping the first step as close as possible to the last step, it reduces the amount of analysis effort the team must perform.

Be careful though, scoping down in this manner still requires discipline to make sure that the primary activities used to create the output are still bounded by beginning/end; and that these reflect the activities that the customer and organization find frustrating and want to improve. If the process boundaries are scoped too small, you can end up excluding root cause areas that should be targeted for improvement. You also run the risk of optimizing some steps but having no positive effect overall.

Boundaries also help to identify other scoping questions. Are there different geographic or site locations that need different process steps? Are there unique customer types or product types that require different process steps? All of these points of confusion are addressed when process mapping.

Clarifying what geographic, customer, or product/service constraints there are, and which ones are in and out of scope, helps remove confusion. By removing confusion, you are creating clarity and that’s the goal of any communication tool, especially a high-level process map.

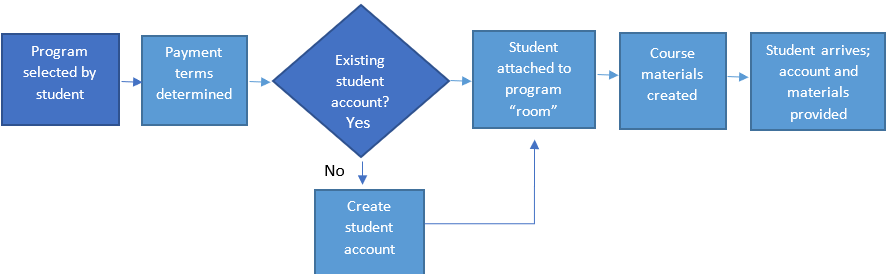

A note on symbols and software: After the beginning and end have been determined, how do you show each of the unique activities or steps that are in the process? For high-level maps, keep it simple. I only use three symbols for high level process maps:

- Boxes: Represent unique process steps or activities

- Diamonds: Represent important decisions, inspection points, rework loops, go/no-go decisions, or a break into parallel simultaneous activities

- Flow Arrows: Connect the boxes and diamonds

Other symbols can and frequently will be used when creating a detailed process map, but since the goal of a high-level map is clear communication, stick to symbols that have intuitive understanding by everyone. The other benefit of these symbols is that square sticky-notes and an erasable writing surface are all that you need to create your first high-level process map. No special software is required yet.

3. Determine the level of complexity

For high-level process maps, we use some of the research on cognitive overload for guidelines on how many boxes to include in the map. These are simple guidelines, and as a result, there may be cases where you need to be flexible and bend the rules. In practice, a high-level map should be:

- Between four to nine activity and decision symbols describing the process

- Fit on a single page using fonts that are readable by anyone

- Follow a linear left-to-right flow (no snake-like flow diagrams which are commonly done to get more than four to nine objects on the page)

4. Have the group sequence the flow

The team works together on determining the sequence of each activity and decision step. Keep in mind that no single person performs all activities, and as a result no single person knows all the activity steps. Group involvement is key when you are working toward developing an accurate process map.

A note on sequencing highly variable processes: In some situations, it will be difficult for the team to come up with a map that describes all of the activities in the process and stick to the rules of four to nine objects. There might be four to nine alternative paths in just the first step.

For example, in Helen’s enrollment process, the team and sponsor agreed to boundaries that began with the customer choosing the program from the website and ended with the customer having all the resources needed for their arrival at the beginning of the program. But when they looked at the first step – choosing the program – here’s what was realized:

- Face-to-face programs have a specific date and location for choosing, but online programs are different, so that means there are two alternative paths from the very beginning.

- Some programs require pre-requisites, so there’s another alternative path and activity box.

- Some programs might be full, but still should be allowed to be chosen because if there’s a demand, a bigger classroom can be reserved. This is yet another alternative path.

- Some online programs can start immediately, there isn’t a start date to see if the student has all the resources they need; yet another alternative path and activity box.

If the high-level map contained all of this information, there wouldn’t be any room left for the other activities and decisions needed to describe the enrollment process. This alternative path information is important but might be better left in a detailed map that is used for analysis rather than communication.

Pro-Tip: Working

When encountering the dilemma Helen’s team had, ask the group to start not from the beginning of the process, but rather from the end and work

Back to the case.

Helen asked the group, “What does the participant get when enrollment is complete?” This was the last step, or boundary, identified earlier as a student login with classroom materials (paper or digital). From there she asked, “What had to happen to get the student login and materials?” Discussion ensued and it was decided that login account creation occurred much earlier and

By working from the back toward the front, the group was able to create a high-level process map that contained the common path. The alternate path details are important for eventual analysis, but at a high-level, everyone has a common understanding of the process. The map is ready to be used as an effective communication tool.

Next Steps

- Identifying stakeholders and systems affected by the process they were investigating.

- Validating the current state. The team “walked the process” to identify missing or incomplete steps and modified the map to reflect what was really happening in

current state. - Using the map during stakeholder interviews so the discussion didn’t get off track. The interviews were a way to collect stories and observations about how the process was currently performing. This type of data collection is called qualitative data collection/analysis.

- Identifying questions that the team had about the stories and observations recorded in earlier interviews. The team identified quantitative or numeric data that was needed to collect, validate, and/or refute stories and observations regarding the current state of performance.

- Focusing and prioritizing which areas of the process the team should concentrate their improvement activities on knowing that they had limited time and resources for the improvement effort. Most improvement efforts don’t have the resources to fix everything that’s an issue in

current state. - Using the map to help with root cause analysis and coming up with future state solutions.

- Comparing the current state map to the future state map of proposed changes and sequencing which activities should be invested in and executed on first.

- Using the future state process map as a visual to help with training and developing new and existing staff and making standard work easier to understand.

As each of these additional activities occurred, Helen and the team made decisions about whether this new information should be added to the simple high-level process map, or whether this new information was less for communication and more for analysis, and as a

If done well, process maps are an excellent way to increase the knowledge level of cross-functional teams. These maps help communicate key ideas to a variety of stakeholders and they help identify areas that need further analysis. They are a great way to visually see your standard operating procedures

Process maps are

Note: This article was originally published in 2019 and updated in 2023.

Scott has developed numerous programs including project management, portfolio management, gathering business requirements, process improvement using Lean Six Sigma, business statistics, and decision making. He also has over a decade of applied experience in the field. Scott has developed programs for a variety of audiences ranging from novices to experienced professionals to C-level executives. Clients have included Fortune 500 firms, the United States military, government, higher education, and not-for-profit agencies. Scott is a Six Sigma black belt and received his M.B.A. from the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He holds a B.S. degree in physics from UW–Eau Claire.